Computer Networks

Learn how computers talk to each other!

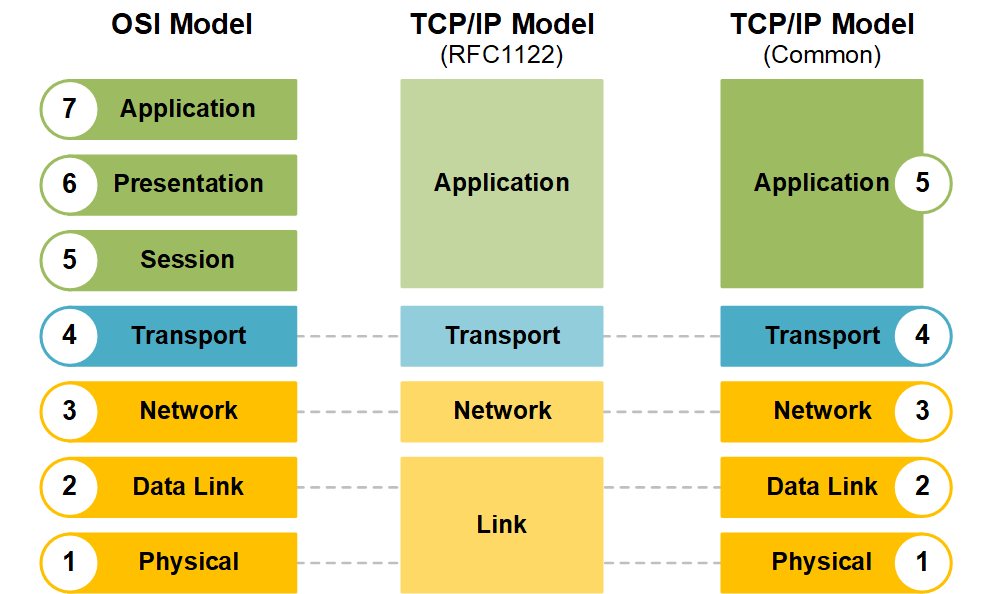

OSI Model

The OSI (Open Systems Interconnection) model is a conceptual framework that describes how data moves through a network, divided into 7 layers:

Layer 1 - Physical Layer

- Function: The physical layer deals with the physical transmission of raw bitstreams over a communication medium (e.g., cables, radio waves, fiber optics).

- Key Elements:

- Transmission media (e.g., twisted-pair cables, coaxial cables, optical fibers)

- Signal types (analog or digital)

- Hardware like network interface cards (NICs), hubs, and repeaters

- Bit synchronization and bit rate control

- Examples: Ethernet cables, Wi-Fi radio signals, USB connections, and modulation methods like Frequency Modulation (FM).

Layer 2 - Data Link Layer

- Function: This layer ensures error-free transmission of data frames between two devices on the same network (local link). It provides link establishment, frame synchronization, error detection, and flow control.

- Key Elements:

- MAC (Media Access Control): Governs how devices on the same network segment gain access to the medium (e.g., using protocols like Ethernet).

- LLC (Logical Link Control): Manages frame synchronization, flow control, and error checking.

- Handles physical addressing using MAC addresses.

- Examples: Ethernet, Wi-Fi (IEEE 802.11), HDLC, PPP, ARP.

Layer 3 - Network Layer

- Function: The network layer handles routing of data across different networks, providing logical addressing and path determination between the source and destination.

- Key Elements:

- Logical addressing (IP addressing)

- Routing: Determines the best path for data to travel across multiple networks.

- Packet forwarding, fragmentation, and reassembly.

- Examples: Internet Protocol (IP), ICMP (Internet Control Message Protocol), OSPF (Open Shortest Path First), and BGP (Border Gateway Protocol).

Layer 4 - Transport Layer

- Function: The transport layer ensures reliable data transfer, manages flow control, error recovery, and data segmentation and reassembly. It establishes end-to-end communication between hosts.

- Key Elements:

- Segmentation: Splitting large data streams into smaller segments for efficient transmission.

- Flow control: Managing the rate of data transmission between sender and receiver.

- Error detection and correction.

- Connection-oriented (TCP) or connectionless (UDP) communication.

- Examples: TCP (Transmission Control Protocol), UDP (User Datagram Protocol).

Layer 5 - Session Layer

- Function: This layer manages and controls the dialog (sessions) between two applications. It handles session initiation, maintenance, and termination.

- Key Elements:

- Session establishment and teardown.

- Synchronization: It can insert checkpoints into the data stream to recover from interruptions.

- Full-duplex or half-duplex communication.

- Examples: RPC (Remote Procedure Call), NetBIOS, PPTP (Point-to-Point Tunneling Protocol).

Layer 6 - Presentation Layer

- Function: The presentation layer is responsible for the translation of data between the application layer and the network. It handles data encoding, encryption, and compression.

- Key Elements:

- Data translation: Ensuring data is converted into a format the application layer can understand (e.g., converting between ASCII and EBCDIC).

- Encryption/Decryption: Ensures secure data transmission.

- Compression/Decompression: Optimizes data size for transmission.

- Examples: SSL/TLS (Secure Sockets Layer / Transport Layer Security), JPEG, MPEG, ASCII, and XML.

Layer 7 - Application Layer

- Function: The application layer is the closest layer to the end-user and interfaces directly with software applications. It provides services such as email, file transfer, and web browsing, and it serves as the entry and exit point for data going into and out of the network stack.

- Key Elements:

- User authentication, authorization, and privacy.

- Provides network services to applications.

- Examples: HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol), FTP (File Transfer Protocol), SMTP (Simple Mail Transfer Protocol), DNS (Domain Name System), Telnet.

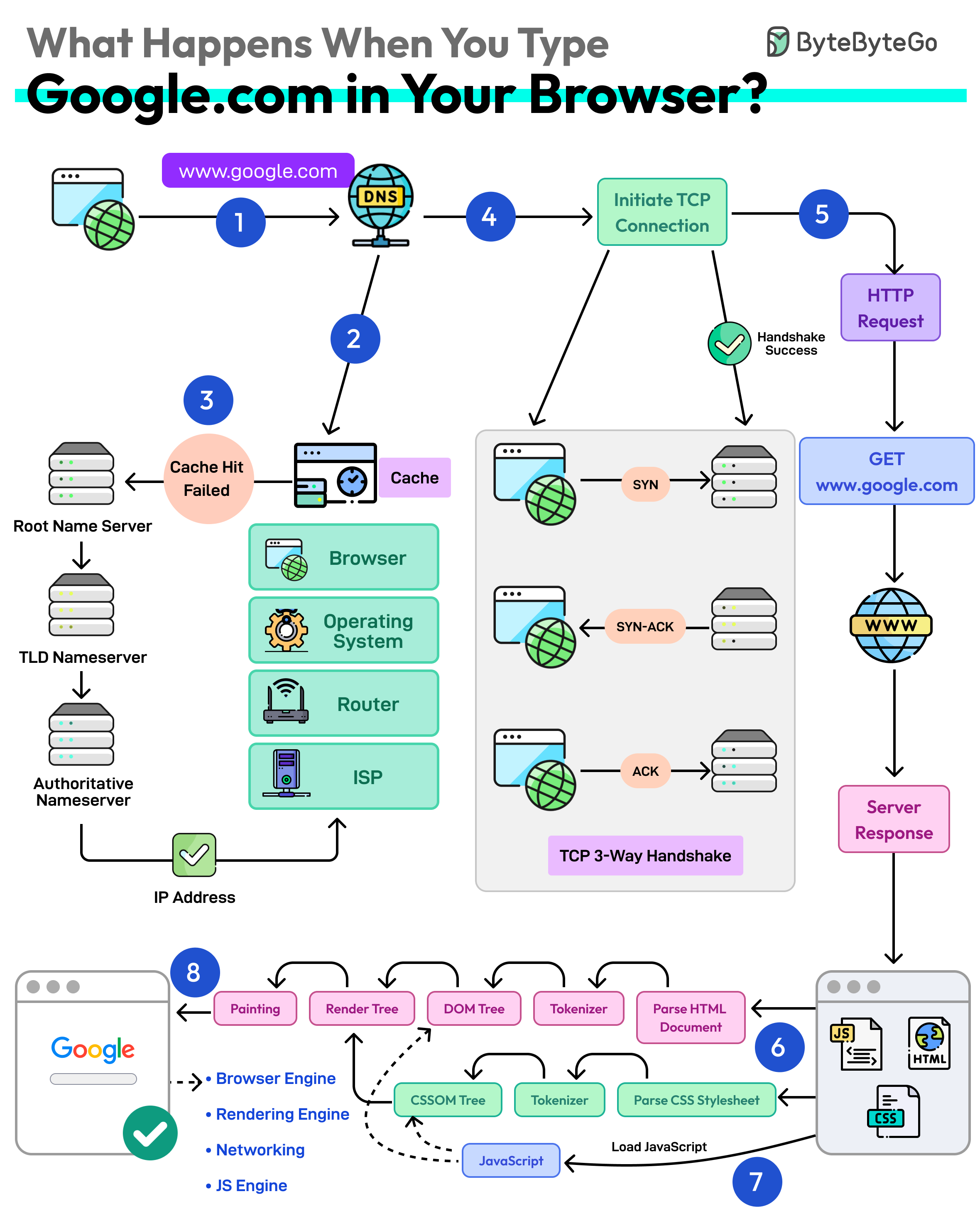

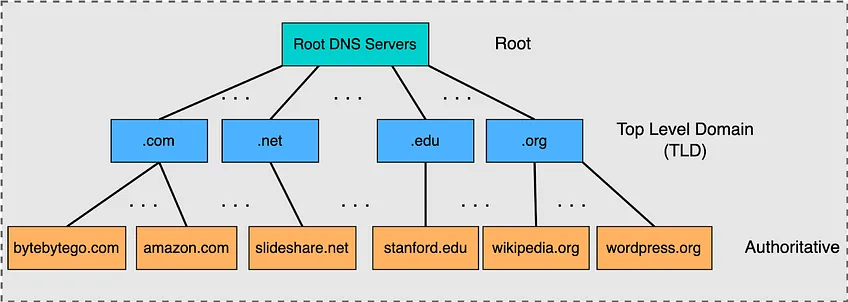

What Happens When You Enter a URL in Your Browser?

- URL -> Universal Resource Locator (scheme://domain:port/path/resource)

- DNS Lookup (translate domain name to IP addresses)

- Browser looks up IP in DNS Cache (Browser -> OS -> Router -> ISP)

- Make request to DNS resolver which resolves via recursive queries to the DNS server (Root -> TLD -> Authoritative Name Server)

- Establish TCP Connection

- May be served via CDN (Content Delivery Network) -> Cache static and dynamic materials closer to the browser

- Use keep-alive connections to reuse an established TCP connection

- If HTTPS -> SSL/TLS handshake -> Use SSL session resumption to lower cost of handshake establishment

- Sends HTTP Request: Over connection to server and receives response to render the webpage

TCP vs UDP

| Aspect | TCP | UDP |

|---|---|---|

| Connection Type | Connection-oriented (requires a handshake to establish a connection) | Connectionless (no handshake, data sent without establishing a connection) |

| Reliability | Reliable (ensures data is delivered in order, without errors, and retransmits lost packets) | Unreliable (no guarantee of delivery, order, or error-checking) |

| Data Transmission | Data is sent as a stream (broken into segments) | Data is sent in individual packets (datagrams) |

| Speed | Slower due to overhead from error-checking, ordering, and retransmission | Faster due to minimal overhead and no need for error-checking |

| Flow Control | Supports flow control to prevent congestion | No flow control, data is sent as fast as the application can send |

| Error Handling | Performs error detection and recovery (retransmits lost or corrupted packets) | No error recovery, though it can detect errors (but doesn’t correct them) |

| Packet Ordering | Ensures packets arrive in order (sequencing) | No guarantee of packet order, which may arrive out of sequence |

| Header Size | Larger header (20 bytes minimum) | Smaller header (8 bytes) |

| Overhead | Higher overhead due to headers for connection management, error-checking, and acknowledgments | Lower overhead, with a simpler header format and no connection management |

| Use Case | Used for applications where reliability and ordered delivery are important (e.g., file transfer, web browsing, email) | Used for applications where speed is more important than reliability (e.g., video streaming, online gaming, VoIP) |

| Applications | Web browsing (HTTP/HTTPS), file transfer (FTP), email (SMTP) | Streaming (video, audio), DNS, gaming, real-time communication |

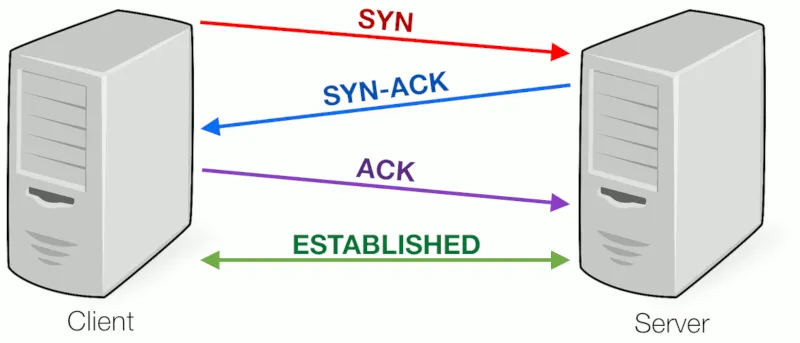

TCP 3-Way Handshake

- SYN (Synchronize):

- The client initiates the connection by sending a TCP segment with the SYN (synchronize) flag set.

- This segment also includes a randomly generated sequence number (say,

x) that will be used to keep track of the bytes in the data stream. - This step signals the server that the client wants to establish a connection.

- SYN-ACK (Synchronize-Acknowledge):

- Upon receiving the SYN segment, the server responds with a segment that has both the SYN and ACK (acknowledge) flags set.

- The ACK acknowledges the client's SYN by setting the acknowledgment number to

x+1, indicating that the server received the client's SYN request. - The server also generates its own sequence number (say,

y) and sends it in the SYN-ACK segment.

- ACK (Acknowledge):

- Finally, the client responds with an ACK segment, which acknowledges the server's SYN-ACK by setting the acknowledgment number to

y+1. - At this point, both the client and the server have synchronized their sequence numbers, and the connection is established.

- Finally, the client responds with an ACK segment, which acknowledges the server's SYN-ACK by setting the acknowledgment number to

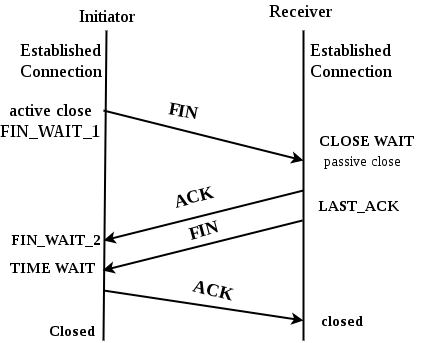

TCP 4-Way Termination

- FIN (Finish):

- The side that wants to terminate the connection (usually the client) sends a FIN segment, indicating that it has finished sending data.

- The FIN flag informs the other side that it should no longer expect data from the sender.

- ACK (Acknowledge):

- The recipient (usually the server) responds with an ACK segment to acknowledge the receipt of the FIN segment. This indicates that it is aware that the connection is closing from the other side.

- At this point, the connection is considered half-closed: the side that sent the FIN can no longer send data, but it can still receive data until the other side closes.

- FIN (Finish):

- If the other side (the server, in this case) has finished its data transmission, it will also send a FIN segment to indicate it is done sending data as well.

- ACK (Acknowledge):

- Finally, the first side (the client) responds with an ACK segment, acknowledging the server's FIN segment. At this point, the connection is fully closed.

Why TCP Termination Requires a 4-Way Handshake?

- TCP is full-duplex: Each direction of the connection (client-to-server and server-to-client) must be closed independently.

- Closure is unidirectional at first: When one side (e.g., client) sends FIN, it indicates "I have no more data to send" but can still receive data.

- Separate acknowledgments needed:

- Client → Server: FIN (request to close outbound direction)

- Server → Client: ACK (acknowledges client's FIN; client's outbound is now closed)

- Server may still have data to send: After acknowledging the client's FIN, the server can continue sending remaining data while the client is in

FIN_WAIT_2state. - Server initiates its own close later:

- Server → Client: FIN (server now has no more data to send)

- Client → Server: ACK (acknowledges server's FIN; server's outbound is now closed)

- Steps 2 and 3 cannot be combined:

- Step 2 (ACK) belongs to acknowledging the client's close request.

- Step 3 (FIN) belongs to the server's independent decision to close its direction.

- These occur at different times, depending on when the server finishes sending data.

- Why not reduce to 3-way (combine ACK and FIN from server)?

- Not always safe or possible: Server might need time to send pending data after acknowledging the client's FIN.

- Combining them would force immediate closure from the server side, potentially losing unsent data.

- Allows graceful shutdown: Server can flush its buffers before closing.

- Additional benefits:

- Clearer state tracking: Easier for both sides to detect issues (e.g. packet loss vs. processing delays).

- Avoids long timeouts: If combined incorrectly, the side waiting for confirmation might timeout unnecessarily.

TCP Congestion Control

TLS/SSL

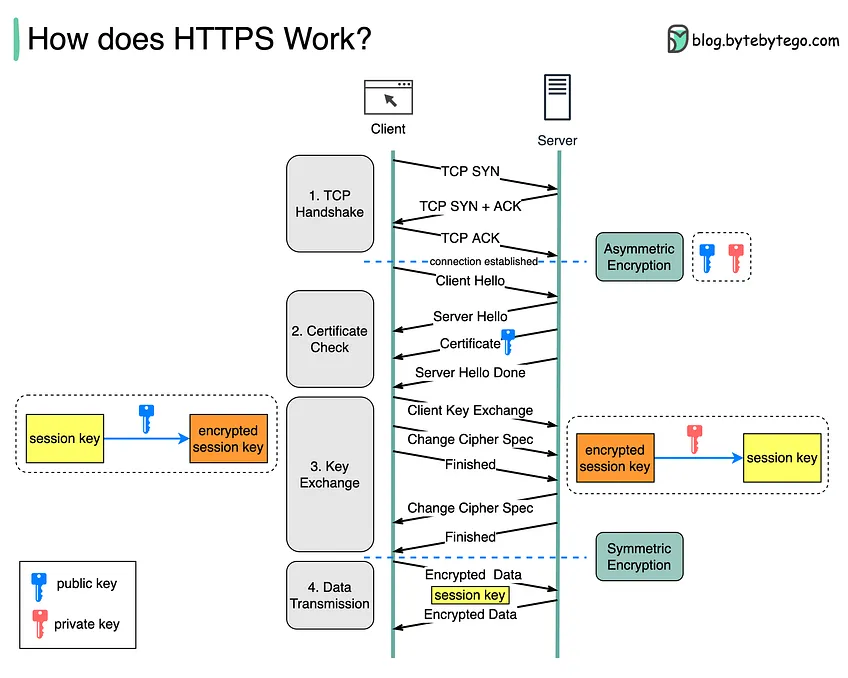

- Client Hello:

- The client (e.g., a browser) initiates the handshake by sending a Client Hello message to the server. This message includes:

- The TLS version the client supports (e.g., TLS 1.2, TLS 1.3).

- A randomly generated client random number, used later for key generation.

- A list of cipher suites (encryption algorithms) the client supports.

- A list of compression methods the client supports.

- Optionally, a list of extensions, such as the Server Name Indication (SNI), which tells the server the domain name the client wants to connect to.

- The client (e.g., a browser) initiates the handshake by sending a Client Hello message to the server. This message includes:

- Server Hello:

- The server responds with a Server Hello message that includes:

- The chosen TLS version (if multiple versions are supported).

- A randomly generated server random number.

- The chosen cipher suite from the list provided by the client.

- The server may also send extensions (e.g., ALPN for protocol negotiation).

- In the next steps, the server's identity is verified to establish trust.

- The server responds with a Server Hello message that includes:

- Server Certificate:

- The server sends its digital certificate to the client. This certificate contains:

- The server’s public key.

- The identity of the server (domain name).

- A digital signature from a trusted Certificate Authority (CA), which the client can verify.

- The client uses the server’s public key to later establish a shared secret and verify the server's identity.

- If client authentication is required, the server will request the client’s certificate (not common in typical web traffic).

- The server sends its digital certificate to the client. This certificate contains:

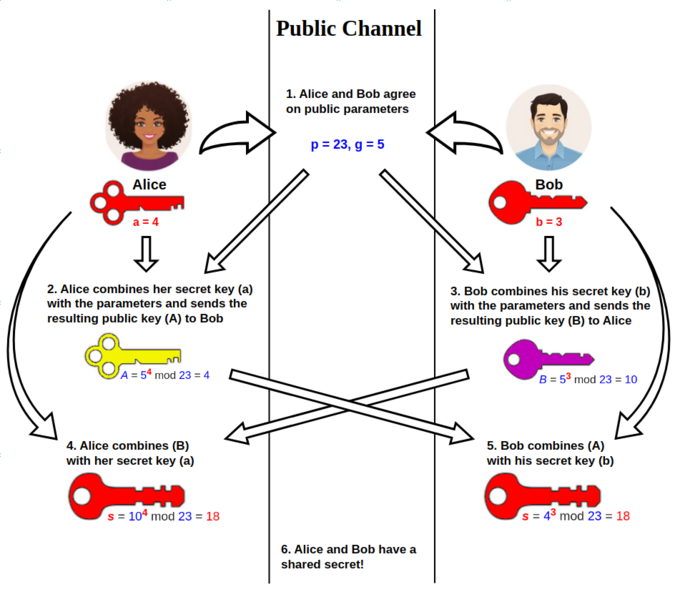

- Key Exchange (TLS 1.2) or Key Share (TLS 1.3):

- TLS 1.2: The client generates a pre-master secret, encrypts it with the server’s public key, and sends it to the server. Both parties use the pre-master secret, the client random, and the server random to generate the session keys (symmetric keys) that will be used to encrypt the communication.

- TLS 1.3: The client and server use Elliptic-Curve Diffie-Hellman (ECDHE) or similar algorithms to securely share a key over the open connection. No pre-master secret is sent; instead, both parties generate shared keys using their private keys and the exchanged public parameters.

- Server Finished:

- The server sends a Finished message, which is encrypted with the session key. This message contains a cryptographic hash of the entire handshake up to this point, ensuring that the handshake hasn't been tampered with.

- Client Finished:

- The client responds with its own Finished message, similarly encrypted with the session key. It also includes a hash of the handshake. Once this is sent, the secure communication is established.

HTTP

0.9

- Overview:

- The earliest version of HTTP, designed primarily for serving static HTML pages.

- It was extremely simple, having only a basic GET method to retrieve data.

- There were no headers, meaning no metadata, status codes, or MIME types.

- Features:

- Only supported text-based content (e.g., HTML).

- No concept of versioning (the version was implied since it was the first standard).

- Connection was closed after each request, making it inefficient for any content beyond simple, static text.

- Use Case: Early web browsing with very basic content.

1.0

- Overview:

- First widely adopted HTTP version, introducing many of the features we associate with HTTP today, like status codes and headers.

- Added methods like POST and HEAD, enabling form submissions and metadata retrieval.

- Features:

- Headers: Allowed clients and servers to exchange metadata (e.g., content type, cache control).

- Status Codes: Introduced the concept of status codes (e.g.,

200 OK,404 Not Found). - MIME Types: Enabled different types of media (images, videos) beyond HTML to be served.

- Connection: After every request, the TCP connection was closed, leading to high latency when loading multiple resources (like images and stylesheets).

- Limitations:

- Every request required a new connection, increasing overhead and making the protocol slower.

- Lacked host header support, which became crucial as web hosting environments started using multiple domain names on a single IP address.

- Use Case: Used during the early expansion of the web when websites became more complex.

1.1

- Overview:

- Most widely used version of HTTP for many years.

- Addressed performance and scalability issues in HTTP/1.0 by introducing persistent connections and pipelining.

- Significant enhancements in caching, error handling, and support for content negotiation.

- Features:

- Persistent Connections: Allowed reuse of TCP connections across multiple HTTP requests, reducing overhead.

- The

Connection: keep-aliveheader enabled a single TCP connection to be used for multiple requests/responses.

- The

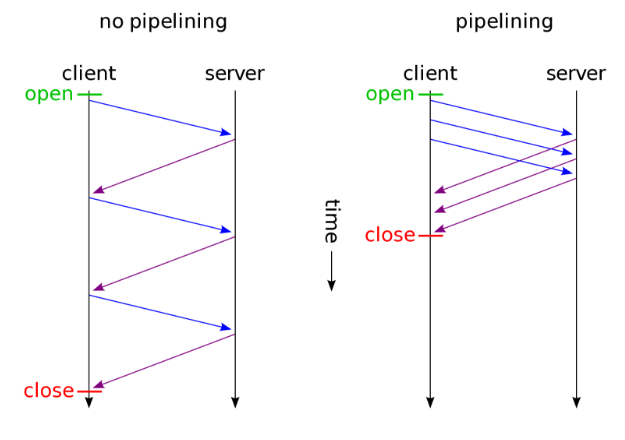

- Pipelining: Allowed multiple requests to be sent without waiting for responses (though it was not widely adopted due to poor implementation).

- Host Header: Enabled hosting multiple websites on a single server with one IP address, facilitating virtual hosting.

- Chunked Transfer Encoding: Allowed servers to send responses in chunks without knowing the full content length upfront.

- Better Caching Mechanisms: Improved use of Cache-Control and ETag headers.

- More Methods: Added methods like PUT, DELETE, and OPTIONS for more versatile interactions.

- Persistent Connections: Allowed reuse of TCP connections across multiple HTTP requests, reducing overhead.

- Limitations:

- Head-of-Line Blocking: If one request in a pipeline is slow, it delays all subsequent requests on the same connection.

- Still text-based, which led to inefficient parsing, higher latency, and bloated requests compared to binary protocols.

- Use Case: This version powered the rapid growth of the modern web and is still in use today.

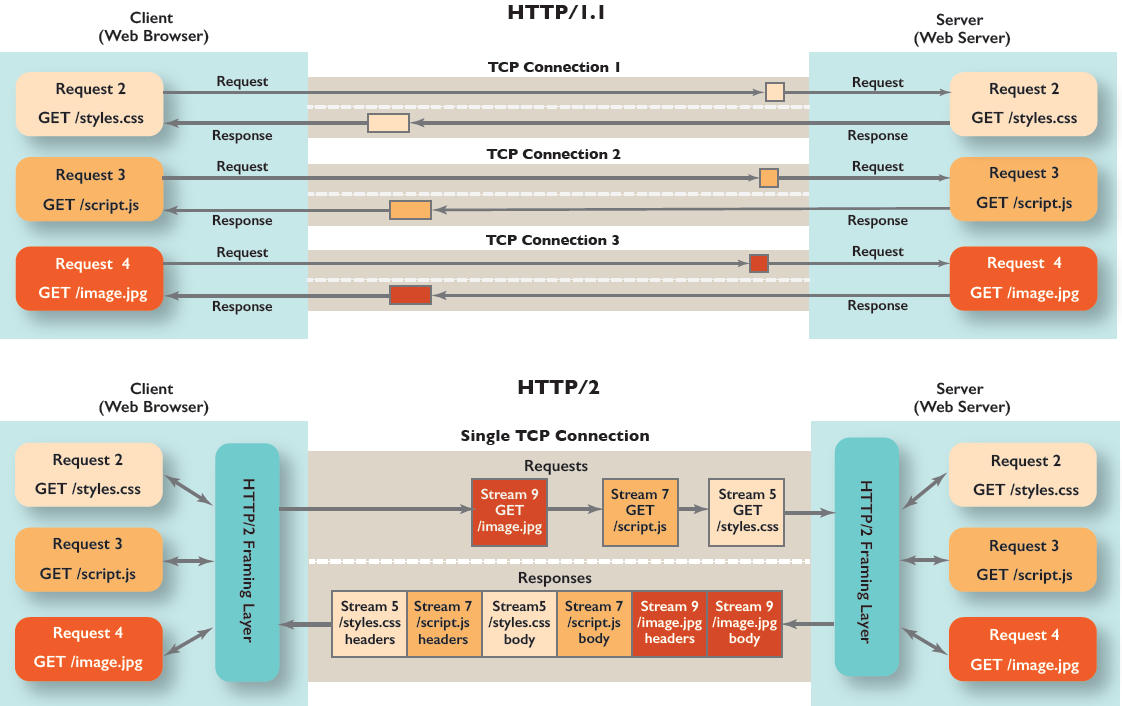

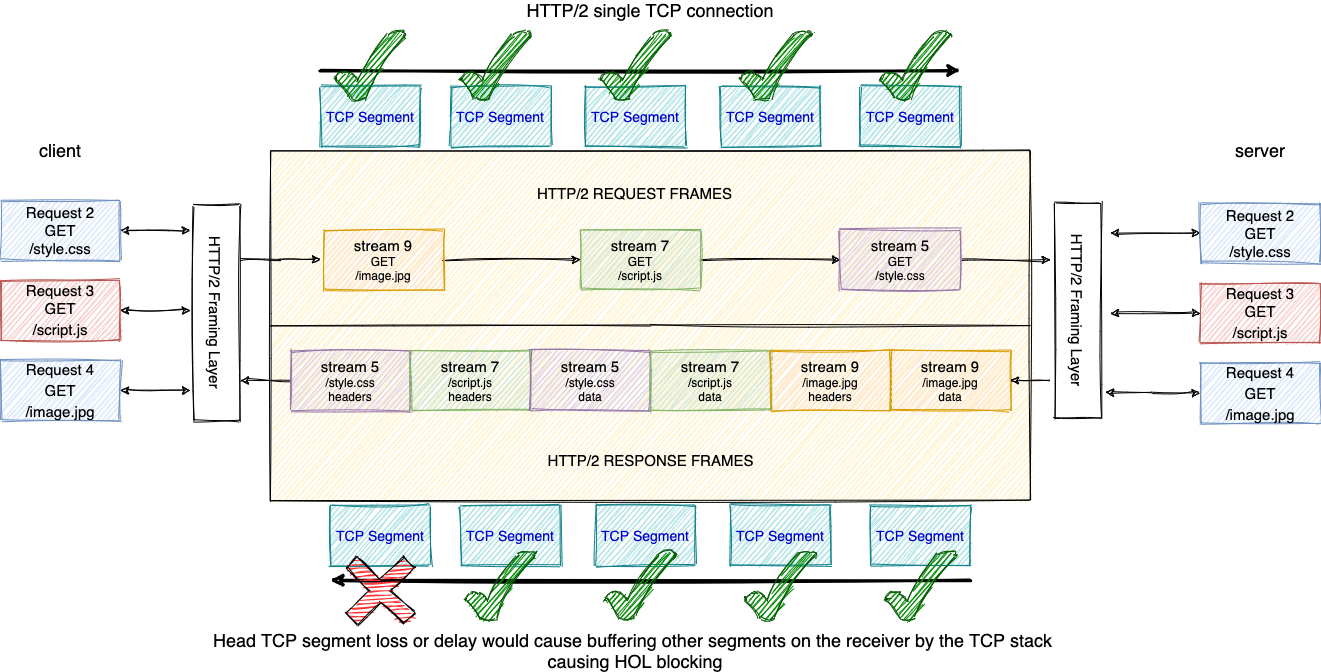

2

- Overview:

- A major revision designed to solve performance issues in HTTP/1.1, especially with regards to handling multiple requests over the same connection.

- Features:

- Binary Protocol: Unlike the text-based HTTP/1.1, HTTP/2 uses a binary framing layer, which is more efficient and faster to parse.

- Multiplexing: Multiple requests and responses can be sent in parallel over a single connection without blocking each other, eliminating head-of-line blocking.

- Header Compression: Uses the HPACK algorithm to reduce the size of HTTP headers, improving performance especially for repeated headers like cookies.

- Server Push: Allows servers to preemptively send resources (like images or stylesheets) to the client before the client requests them, reducing latency.

- Stream Prioritization: Allows clients to prioritize resources, so critical content (like HTML) is downloaded before less important content (like images).

- Persistent Connections: Further refines the concept of persistent connections introduced in HTTP/1.1 by allowing multiple simultaneous requests over a single connection more efficiently.

- Limitations:

- Requires encryption in most modern implementations (though it’s technically not mandatory in the spec, HTTPS is used almost exclusively).

- While it solved many issues of HTTP/1.1, it is still built on top of the same TCP layer, which can introduce head-of-line blocking at the TCP level.

- Use Case: HTTP/2 is widely supported by modern browsers and is used by websites to improve performance, especially in loading complex pages with many resources.

3

- Overview:

- Built to address the limitations of HTTP/2 by using QUIC (Quick UDP Internet Connections) as its transport layer instead of TCP.

- QUIC was initially developed by Google and later standardized by the IETF.

- Features:

- QUIC Protocol: Replaces TCP with QUIC, which is built on UDP. QUIC reduces latency by eliminating the need for a handshake before sending data and reducing head-of-line blocking at the transport layer.

- Zero Round Trip Time (0-RTT): With QUIC, there’s no need for a full handshake for repeat connections, allowing encrypted communication to start immediately.

- Stream Multiplexing without HOL Blocking: QUIC allows independent streams within a connection, meaning that if one stream experiences packet loss, it doesn’t block the others.

- Connection Migration: QUIC allows connections to seamlessly migrate between networks without interruption (e.g., switching from Wi-Fi to cellular).

- Improved Security: Encrypted by default (built on TLS 1.3), providing better security and privacy.

- Limitations:

- QUIC requires broader adoption and more complex server infrastructure to fully take advantage of its capabilities.

- Some middleboxes (like firewalls and routers) may not yet fully support QUIC, which can cause issues in certain network configurations.

- Use Case: HTTP/3 is designed for modern web applications with high performance, low-latency requirements, and is being adopted by major platforms like Google, Facebook, and Cloudflare.

WebSockets

Protocol designed to provide full-duplex (two-way) communication channels over a single, long-lived TCP connection

- Key Features:

- Full-Duplex Communication:

- Both the client and the server can send and receive messages at any time without having to wait for each other, allowing for real-time data transfer.

- Persistent Connection:

- A WebSocket connection is established once and stays open for the duration of the interaction. This reduces the overhead associated with establishing multiple HTTP connections (e.g., via polling or long-polling).

- Low Latency:

- WebSockets reduce the latency associated with traditional HTTP, where each request would need to establish a new connection. With WebSockets, data can be pushed in real-time with minimal delay.

- Lightweight Header:

- WebSocket frames have much smaller headers compared to traditional HTTP messages, making communication more efficient, especially for frequent updates.

- Binary and Text Data:

- WebSockets support both text (UTF-8) and binary data transmission, providing flexibility for different types of data.

- Full-Duplex Communication:

- The WebSocket connection starts with a HTTP handshake (an

UPGRADErequest) to establish the connection, after which the protocol switches from HTTP to WebSocket. Here's how it works:- Client Request:

- The client sends an HTTP request to the server with a special

Upgradeheader, requesting to upgrade the connection to WebSocket. The request typically looks like this:

GET /chat HTTP/1.1

Host: example.com

Upgrade: websocket

Connection: Upgrade

Sec-WebSocket-Key: x3JJHMbDL1EzLkh9GBhXDw==

Sec-WebSocket-Version: 13

- The client sends an HTTP request to the server with a special

- Server Response:

- If the server supports WebSockets, it responds with an HTTP 101 status code to switch protocols:

HTTP/1.1 101 Switching Protocols

Upgrade: websocket

Connection: Upgrade

Sec-WebSocket-Accept: HSmrc0sMlYUkAGmm5OPpG2HaGWk=

- If the server supports WebSockets, it responds with an HTTP 101 status code to switch protocols:

- Persistent WebSocket Connection:

- Once the handshake is complete, the HTTP connection is upgraded to a WebSocket connection, and both the client and server can begin to send and receive messages through the open channel without the overhead of HTTP requests.

- Client Request:

- Use cases: Real-time applications, online gaming, collaborative tools, live feeds

IPv4

IPv6

DNS

- There are two main methods of query resolution in DNS:

- Iterative query resolution

- Recursive query resolution

NAT

UDP Hole Punching

BGP

OSPF

Anycast / Multicast

ARP

VRRP

Wireguard

- IPv6

- GUA -> Global Unicast Address (2000/3)

- ULA -> Unicast Local Address (fc00/7)

- How does Virtual Private Network (VPN) do IP switching?

- Allows users to change or "switch" their IP addresses by creating a secure, encrypted tunnel between the user’s device and a remote VPN server.

-

Process of VPN IP Switching:

- User Connects to a VPN Server:

- When a user initiates a connection to a VPN, the VPN software on the user’s device (VPN client) establishes a secure connection to one of the VPN provider’s remote servers located in a different geographical region. The VPN client encrypts all traffic sent from the user’s device.

- VPN Server Assigns a New IP Address:

- The VPN server assigns the user a new public IP address that corresponds to the server’s location. For instance, if the user connects to a VPN server in France, they will be assigned a French IP address. This is the IP address that will be visible to websites and services the user interacts with.

- IP Masking:

- The VPN server hides the user's original IP address by acting as an intermediary. All internet traffic is routed through the VPN server, making it appear as though the requests are coming from the VPN server’s IP address instead of the user’s original IP.

- Routing of Internet Traffic:

- When the user sends a request (such as visiting a website), it first goes to the VPN server. The VPN server forwards the request to the destination (the website or service), using the VPN-assigned IP address.

- The response from the website is then sent back to the VPN server, which decrypts it (if necessary) and forwards it to the user. Throughout this process, the user's real IP address remains hidden, and only the VPN server's IP is exposed.

- Dynamic IP Switching:

- Some VPN services provide the ability to switch between different VPN servers manually, which effectively changes the user's public IP address to match the location of the new server. For example, switching from a server in the US to one in the UK will change the user’s IP address from a US-based IP to a UK-based one.

- IP Rotation:

- Certain VPN providers may offer dynamic IP rotation, where the VPN server periodically assigns a new IP address to the user during the same session. This adds an extra layer of anonymity, as the user’s apparent IP address keeps changing.

- User Connects to a VPN Server:

-

How VPNs Achieve IP Switching:

- Network Address Translation (NAT):

- VPN servers use NAT to translate the user’s private IP address (assigned by their local network, e.g., 192.168.x.x) into the VPN server’s public IP address. All the traffic appears to originate from the VPN server’s IP, effectively masking the user’s true IP.

- Encryption:

- VPNs secure all communication between the user’s device and the VPN server using encryption (such as AES-256). This ensures that even if someone intercepts the traffic, they won’t be able to see the user’s original IP address or the content of their data.

- Geolocation:

- By choosing VPN servers in different countries, users can effectively change their virtual location. Websites and services will think the user is located wherever the VPN server is based, allowing the user to access region-restricted content or appear to be in a different country.

- Network Address Translation (NAT):